As New Joy Mart marks its 18th anniversary, the path ahead has become increasingly clear.

In the first half of this year, New Joy Mart expanded beyond Hunan and accelerated its growth in Hubei. Of the more than 200 new stores, nearly half were opened in Hubei. In cities such as Yichang, Xianning, and Ezhou, New Joy Mart quickly rose to a leading position upon its entry. Staying true to its positioning as “a neighborhood milk shop + breakfast shop + coffee shop” and maintaining a steady pace of 50–70 new stores per month, New Joy Mart’s strategic depth across Central China is becoming increasingly evident.

Looking back over the past 18 years, founder Minyi Wu believes New Joy Mart’s growth stemmed from three decisive choices: abandoning fragmented franchise models, focusing on lower-tier markets, and developing private-label products.

Behind each of these decisions lay short-term challenges, opportunity costs, and a difficult balancing act between entrepreneurial ambition and market demand. What is truly hard about doing the difficult but right thing is not making the decision itself, but maintaining the perseverance to see it through.

Fortunately, New Joy Mart has earned the market’s trust through 18 years of perseverance. It has shattered the stereotype of convenience stores as “exclusive to the middle class” and “overpriced,” and has thrived by focusing on lower-tier markets. With resolute determination, it abandoned the fragmented franchise model, adopting a tightly managed franchise approach to safeguard product quality and lay a foundation for healthy expansion. It weathered the early losses of private-label development, and ultimately enabled county-level consumers to enjoy “convenience store freedom” with products like RMB 3.9 per jin fresh beer, RMB 4.9 for 500ml fresh milk, and RMB 4.9 Americanos.

The development of convenience stores in China began in the 1990s, when international brands such as 7-Eleven, Lawson, and FamilyMart entered the market. They brought advanced management expertise and operating models that inspired China’s domestic convenience store industry. With rapid economic growth and accelerating urbanization, China’s convenience store chains have experienced a period of explosive expansion over the past decade, with the number of stores surging from 20,000 to over 300,000.

Amid this surging wave of convenience stores, New Joy Mart stands out as something of an “outlier.” In terms of product selection and pricing, it is more grounded and accessible than many international chains, with a steadfast focus on value-for-money. In store operations and franchisee management, it is more assertive than traditional domestic chains, with strict control as its core approach. Unlike conventional retailers who focus solely on procurement and resale, New Joy Mart offers more than 100 private-label products in its stores—accounting for just 10% of SKUs but contributing over 20% of sales.

In many ways, New Joy Mart is more than a convenience store. It serves as a community provider in lower-tier markets and as a manufacturing-oriented retailer—investing heavily in its supply chain to bring high-quality fresh milk, juice, and coffee into the homes of everyday consumers.

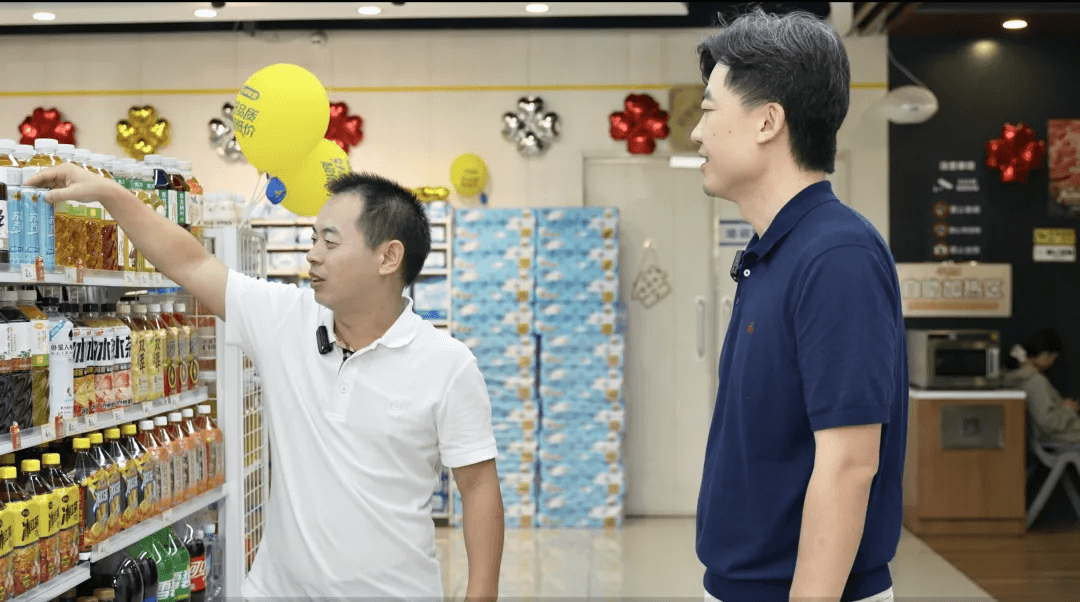

On July 11, coinciding with New Joy Mart’s 18th anniversary, we visited its headquarters in Changsha. Victor Zhang, Founding Partner of GenBridge Capital, held an in-depth conversation with founder Minyi Wu, covering New Joy Mart’s entrepreneurial journey, key strategic decisions, and future outlook. The following is a selection of highlights from their two-hour dialogue:

Review of entrepreneurial journey

Victor Zhang: I am very pleased that on this special 18th anniversary, we can look back together at the 18-year journey of New Joy Mart. Let us start from the beginning—Mr. Wu, how did you transition from being a doctor to entering the convenience store industry?

Minyi Wu: Time really flies! I used to work in a hospital, but I felt that my professional development had reached a bottleneck. At that time, I wanted to pursue something relatively simple while still creating personal value. I thought opening a small shop would not be too difficult, so I gave it a try. Only later did I realize that running it well was far from easy.

My entry into the convenience store industry and my path to where we are today was, in fact, somewhat accidental. In the first two years, we went with the flow and opened six stores. Then some of my partners asked whether we could build a brand together. From there, we gradually grew to a dozen, then dozens of stores. Step by step, we moved forward—though not without stumbling into many pitfalls along the way.

Victor Zhang: When did you encounter the first major setback, and what adjustments or reflections followed?

Minyi Wu: From 2007 to 2016, our growth was very smooth. Driven by both the market and franchisees, our scale essentially doubled every year, and soon we had reached 1,000 stores. However, during this process of developing a chain, both our logistics and product systems experienced problems, and we also made many missteps in personnel management.

In fact, before 2016, I did not even understand what a true convenience store was, and no one in the company had retail experience. Later, when I observed brands like 7-Eleven and Lawson, and participated in industry events and overseas study tours, I realized that within the small-format retail segment there was an entire “convenience store” industry, and that so many stylish international brands were operating successfully. I felt at that time that this was a very promising direction—strong brand image, popular with consumers, and capable of achieving large scale.

Victor Zhang: After gaining this understanding of the convenience store model, what actions did you take?

Minyi Wu: Motivated by our aspiration for this store format and brand image, we engaged a consulting team from Taiwan. They helped us build our product system, improve cold chain logistics, and establish store SOPs, bringing the Taiwanese convenience store model to Changsha and opening several stores. We also launched our first fresh-food directly operated store. The image and atmosphere we created were good, but profitability was lacking. This was both an interesting and very real challenge, but we did not give up. We then began reflecting on how to adapt the model to China’s local conditions.

At that time, many branded convenience store chains were ramping up investment. The daily sales of our store format were decent, reaching RMB 8,000 to 10,000. However, the cost structure of back-end support and front-end gross margins made profitability difficult. This raised a key question for us: if we continued competing in this way, and our convenience stores lacked a distinctive edge, why would consumers choose us? Previously, we had relied on franchising to build scale, but was that truly the path forward? With competition in ambient goods intensifying, could the cold chain become a breakthrough?

Our goal was to create a small-format store that looked attractive, was favored by consumers, could generate profit for franchisees, and offered a sustainable future for the company. Yet the number of feasible directions available to us was limited.

Transformation of franchise model

Victor Zhang: From 2018 to the first half of 2019, New Joy Mart was still in the exploration stage. At that time, you continued to open directly operated stores, while also facing many challenges. Looking back, how did the company transition from the direct operation model to today’s franchise system?

Minyi Wu: Between 2018 and 2019, our fresh-food directly operated stores expanded from just over 20 to nearly 200, with fairly strong daily sales. But we also realized that imitation had limited long-term value—we wanted to build our own unique advantage. So, while operating directly managed stores, we simultaneously explored different paths in terms of categories, cities, and formats, searching for a better solution.

In the second half of 2019, we began experimenting with several franchise formats. By the end of the year, we had identified a simplified, strong-control franchise model that suited us. In 2020, when the pandemic struck, our directly operated stores had not yet achieved profitability, and it was the franchise stores that sustained the company. Ironically, this gave us the breathing space to pause cash burn, reorganize operations, and refine the model. By the end of 2020, we officially launched the development of the new franchise format, piloting a dozen or so stores. It was not until 2021 that we began full-scale promotion. Since then, more than 1,000 stores opened in the past three years have all adopted this model.

Victor Zhang: Could you elaborate on how our final franchise model differs from others?

Minyi Wu: Our franchise system is quite different from both Japanese-style models and the fragmented franchise models common in China.

Fragmented franchising differs greatly from direct operations. Franchisees may independently decide pricing, marketing, and service, and can even source products themselves. This was essentially our first-generation franchise model—a fragmented approach. By contrast, the Japanese system follows an entrusted model rather than a traditional franchise, operating on a profit-sharing basis in which both the franchisor and franchisee invest, and profits are allocated according to a fixed proportion of gross margin or sales.

Our current model, however, allows franchisees to keep all the profits. We, in turn, earn through optimizing margins and efficiency across the entire value chain. This includes building our own logistics, upgrading systems, cultivating agents, and developing private-label products. Inevitably, this required upfront losses before scale was achieved. But for consumers, under our tightly managed franchise system, the in-store assortment, pricing, promotions, service, and even online experience are entirely consistent with our directly operated stores.

For franchisees, store assets and staff belong to them, but all they need to do is follow our professional guidance to execute company standards—serving customers well, managing the store, and handling daily operations. This approach significantly reduces the risk of losses.

Ultimately, if one hopes to prevail in the future, it is necessary to think, design, and experiment independently from the ground up. Although the process is slower and often painful in the early stages, the long-term value far outweighs mere imitation.

From core products to private label

Victor Zhang: Before developing a franchise model that worked for franchisees, you always hoped that they could achieve reasonable returns. In 2018, with the directly operated system, some stores were profitable and others were not, leaving limited room for franchisee profits. So in early 2019, we discussed how to improve store formats and enhance profitability.

At the strategic meeting, we explored possible breakthroughs starting with categories. Among three to five candidate categories, we considered feasibility, our own capabilities, and barriers to entry, and unanimously decided to make fresh milk the critical battle for 2019. Mr. Wu, could you share how fresh milk paved the way for further category expansion at New Joy Mart?

Minyi Wu: At that time, it was difficult to establish advantages in ambient goods, so we considered whether cold-chain categories might present opportunities. If so, where would those opportunities lie?

Most of the low-cost technologies and factory resources for fresh food production were concentrated in the hands of Japanese brands, while coffee was a capital-intensive project. We decided to shift from ambient categories toward chilled products, ultimately focusing on dairy. From a market perspective, annual ambient milk sales in Hunan were close to RMB 10 billion, but fresh milk accounted for less than 1% of that total. We judged this to be a significant growth opportunity.

Fresh milk has seasonal fluctuations, and we suffered heavy losses in the first year. But based on our early hypotheses and strategic focus, we persisted—continuously refining our algorithms, systems, and logistics, and building out cold-chain infrastructure. Over time, the fresh milk business entered a period of rapid growth, with sales doubling annually. Today, the fresh milk market in Hunan is nearly RMB 1 billion, and we hold a 30–40% market share, giving us a dominant position.

Victor Zhang: After the success of the dairy business, many people in Hunan and Changsha bought their first fresh milk at New Joy Mart. At that time, how much incremental contribution did this category make to a single store?

Minyi Wu: Fresh milk accounted for about 5% of sales, but more importantly, consumers perceived our milk as fresher, which attracted traffic. Building on the dairy business, we gained opportunities to expand into other categories, such as creating breakfast scenarios around fresh milk or combining fresh milk with coffee.

Victor Zhang: Our first private-label product was milk. How did we then evolve into today’s strategy of launching a “hero product” every month?

Minyi Wu: When we started the fresh milk business, to break through the ceiling we had to offer products superior in quality and better priced than others. This required moving from sourcing through agents to producing ourselves. We inspected the top ten milk-producing regions and numerous factories across China, and ultimately selected highland milk sources in Ningxia, processed in Guizhou, and transported in full loads via our own logistics system to Changsha.

Instead of the usual 400 ml carton, we packed 500 ml of fresh milk, priced it at RMB 4.9, and ensured freshness levels ten times higher than premium brands like Telunsu. Under these conditions, sales volume for comparable products increased tenfold. This showed us that consumers do not care only about brand names, but about value-for-money—especially in county-level markets.

We insisted on sourcing from the best domestic farms and personally inspecting them. From cattle feed and raw materials, to milking procedures, every detail was scrutinized—cows had to be cleaned before milking, inspected for injuries, and each milking step carefully controlled for precision, temperature, time, and hygiene. The quality control process for milk is complex, but it is essential to producing high-quality fresh milk.

Victor Zhang: When New Joy Mart first started selling fresh milk in 2019, the company was only familiar with national dairy brands. Today, we are discussing the care and milking practices of cows at China’s best farms. This transformation from retailer to manufacturing-oriented retailer is a microcosm of the company’s evolution.

Minyi Wu: Compared to traditional supermarket brands, our private-label development focuses much more on the product itself, not just rebranding generic goods while neglecting quality control. The logic of our private-label strategy is to move slowly at first, then accelerate once we build knowledge through practice.

We began private-label development in 2019, and I see it as progressing in phases. The first phase was experimentation—starting from nothing, learning how to build a private label. At first we followed the models of Hema and Sam’s Club, focusing on categories and temperature zones where we had advantages, such as fresh milk, fresh beer, and iced beverages, leveraging our cold-chain logistics.

The second phase was about affordability. Our private-label products were priced at 30–50% below the market, sometimes even lower. We did not price based on competition, but on consumer demand and purchasing power, since our target customers in smaller cities have limited budgets. We wanted to make products affordable and encourage repeat purchases.

This year, our priority is to ensure that quality is consistently and significantly above the market average, shifting from “cheaper” to “better.” We only launch large-scale hero products and avoid low-volume items. To support this, we built R&D and quality control teams to guarantee product quality and stability.

To date, we have developed more than 200 private-label SKUs, with around 100 on sale in stores at any given time. These account for roughly 10% of SKUs but contribute more than 20% of sales. Compared with last year, same-store sales have risen by 6–10 percentage points, mainly driven by private-label products. Sales of national brands are reaching saturation, and in many cases are declining.

Last month alone, 77 new franchise agreements were signed, nearly doubling the pace of store openings year-on-year. This demonstrates recognition of our model. In today’s highly competitive market, many franchisees selling the same products struggle more and more, and lose confidence. But when they see our products with clear advantages in value-for-money, volume potential, and consumer appeal, they naturally become more confident in operating their stores.

Expansion strategy and future outlook

Victor Zhang: For many years we focused on Hunan. When did New Joy Mart first expand beyond the province?

Minyi Wu: We went to Jiangxi at the end of 2023, opening dozens of stores in prefecture-level cities such as Pingxiang and Yichun. Now we are expanding northward into Hubei.

At present, since entering prefecture-level cities in 2022 and counties in 2023, growth in these markets has been faster than in provincial capitals, reaching 40–50%. We have already opened more than 100 stores in Hubei, but none in Wuhan. This is because outside Wuhan, prefecture-level cities in Hubei have relatively shallow convenience store penetration and weaker competition. Within three to six months of our entry, we quickly ranked among the leading 24-hour convenience store chains in terms of daily sales, number of stores, and growth scale.

We believe that in the coming years, maintaining high-quality growth will depend on leveraging our operational capabilities to drive cross-regional development. This involves three key factors: first, capabilities, such as logistics development and frontline talent, and whether we can allocate top resources to market expansion; second, profitability, which must surpass even that of mature markets; and third, long-term sustainability, ensuring franchisees remain profitable, company capabilities are aligned, and development pace and density are balanced to create a virtuous cycle.

Essentially, it means “fishing where the fish are”—going where both consumers and franchisees need us, and where our capabilities can match. It is about not only doing the right things but doing them well. The process requires following demand, abandoning unrealistic ambitions, and expanding gradually from county to county. From Hunan to Jiangxi, Hubei, and surrounding smaller cities, these markets are only tens of kilometers apart, so there is no need to rush.

Victor Zhang: Many traditional approaches would first target a provincial capital before expanding to surrounding areas. But when we entered Hubei, we focused on cities around Wuhan without entering Wuhan itself. What was the reasoning?

Minyi Wu: People often ask me when we will enter Nanchang or Wuhan. In fact, we already have stores in nearly 60 cities. For example, going from Changsha to Chenzhou or Yichang requires a round trip of more than 1,000 kilometers—farther than Nanchang or Wuhan—and these markets are smaller, with lower consumer purchasing power and higher operating difficulty.

But by making decisions based on actual demand, we found these were the right choices. Many of these cities lacked sufficient supply of products and services, and consumer needs were unmet. We were able to provide better choices, higher-quality goods, and more reasonable prices. For local franchisees, options were limited, and local distributors lacked strong partners offering premium brands and services.

We have operated a logistics center in Wuhan for six months, yet we have not opened a single store there. In surrounding prefecture-level cities, we are already among the best, but that alone is not enough. Our goal is to become the most value-for-money retail brand in lower-tier markets, enabling consumers to access higher-quality, affordable products and improve their quality of life. We must ensure that franchisees and stores in Hubei can one day match the performance and profitability levels of those in Hunan—this is our non-negotiable commitment.

Victor Zhang: Looking ahead three to five years, how many regions will we cover?

Minyi Wu: Our ultimate long-term goal is to become the most valuable retail service brand for consumers in smaller cities. Geographic coverage is not our primary metric. In terms of expansion pace, the exact number of cities is still under observation. What we care more about is how the market evolves over the next five to ten years and which areas we will have the opportunity to enter.