After enjoying thirty years of prosperity, the grand circulation system is now heading toward decline. Once-dominant supermarkets are struggling to survive, and across the country, the retail industry is experiencing a wave of adjustments and reforms.

When the consumer market shifts from an era of incremental growth to one of stock competition, the traditional seller-centered solutions, which once focused on deep distribution, have become ineffective. The retail industry urgently needs to transform its operating approach and find solutions from the buyer’s perspective.

Looking at the history of global retail, we can see that the companies able to weather cycles and win in buyer-driven markets all share one common trait: they place great importance on managing product categories.

For example, when Japan entered a mature, saturation market in the 1990s, standout players like Kobe Bussan and LOPIA rose to prominence by becoming “category killers”, Kobe Bussan with affordable frozen foods, and LOPIA with competitively priced meats.

Even comprehensive formats like 7-Eleven and Trader Joe’s owe their success to excellent category management. 7-Eleven, for instance, escaped the post-bubble economic slump by focusing on a “fresh food” strategy, eventually becoming Japan’s largest food company. Trader Joe’s, on the other hand, disrupted the U.S. distribution sector in the 1980s by narrowing its product range, slashing hundreds of SKUs to focus only on products with clear customer value, and starting with its breakthrough in the wine category. It became known as the “king of sales per square foot” in retail.

Beyond practice, theory has followed suit. Brian Harris’s Category Management, Tetsuo Suzuki’s 52-Week Merchandising (MD), and Toshifumi Suzuki’s single-item management theory all focus on the study of categories.

All these cases prove one thing: category management is an essential solution when shifting the retail mindset from the seller’s perspective to the buyer’s. In a stock-driven era, whether a company can manage its categories well almost determines its survival or failure.

Why does category management determine success in a mature market?

First, at its core, category management is a buyer-centric approach, rooted in consumer needs.

In a supply-constrained, incremental market, retailers use traditional models: they manage by brand, focusing on negotiations with suppliers and allocating limited shelf space. But in a mature market, power shifts from the supply side to the demand side. Within a single category, dozens of brands may compete, and products are often highly substitutable. This forces retailers to pay close attention to what consumers actually want.

In a world of diverse, segmented consumption, consumer demand essentially follows a quantified decision tree. Take dining as an example: time, location, purpose, lifestyle — each layer forms a decision node that branches into multiple possibilities.

In a world of diverse, segmented consumption, consumer demand essentially follows a quantified decision tree. Take dining as an example: time, location, purpose, lifestyle — each layer forms a decision node that branches into multiple possibilities.

Category management is based on this premise. A “category” is not something retailers come up with arbitrarily; it’s carefully structured based on the consumer’s decision tree. It requires retailers to deeply understand consumption scenarios and constantly monitor whether consumer needs at each decision branch are being met.

When Trader Joe’s developed its wine category, it followed this principle. The supermarket targeted educated, tasteful, but not particularly wealthy consumers, offering them high-quality yet affordable wines. To do so, Trader Joe’s eliminated 100 Scottish whisky brands, 70 bourbon brands, 50 gin brands, and countless boutique Californian wines, which kept only those with a clear price advantage or exclusive value. They even imported niche brands, ensuring their offerings remained trustworthy in the eyes of consumers.

Today, we see similar strategies at Sam’s Club, all designed to prove to customers: our products are always worth your trust.

Second, category management places all players along the supply chain in the same arena, transforming the relationship between brands and channels from a zero-sum game into mutual collaboration.

According to Brian Harris’s category management theory, if a brand wants to launch a new product, it must prove the incremental value it brings to the category, avoiding shelf space cannibalization with homogeneous products. Channels, on the other hand, need the manufacturing capabilities of brands to strengthen the category’s structure and competitiveness.

As a result, channels and brands are no longer mere opponents across a negotiation table; they become co-developers in product creation. For any given product, from major issues like traffic, gross margins, and consumer expansion, down to visual merchandising and marketing strategies, both sides must communicate early and jointly assess market demand.

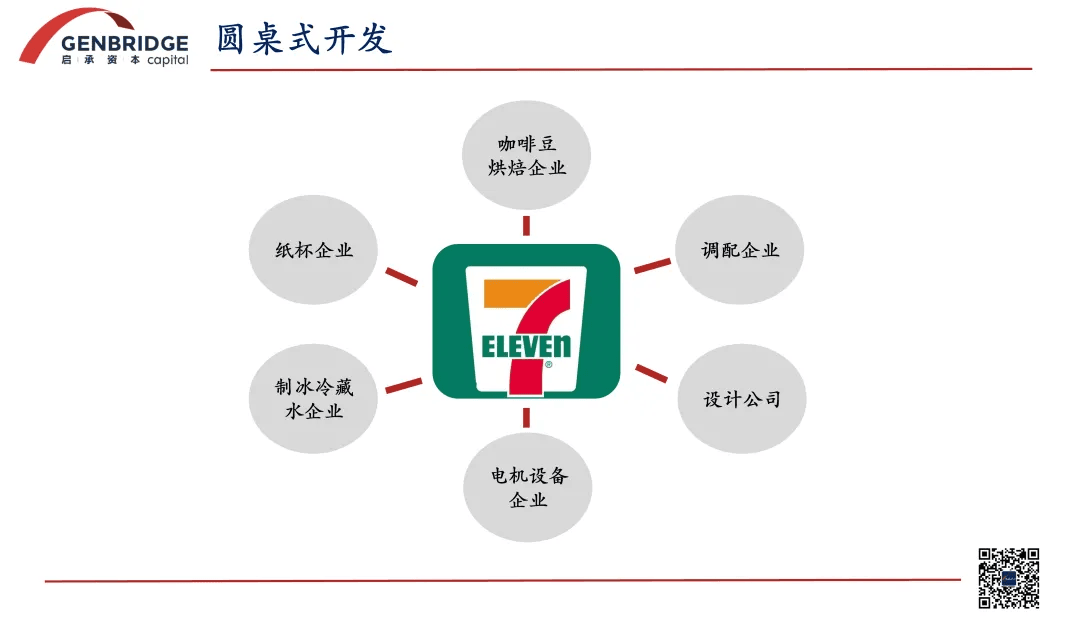

This collaborative process also shortens what was once a long, cumbersome supply chain. Channels work directly with manufacturers or brands, gradually moving away from slotting fees and barcode fees, distributing profits more reasonably, and cooperating long-term under refined category planning schemes. In Japan, some retailers have even adopted roundtable-style development structures to further boost efficiency.

We can see that this is precisely the general direction driving the current wave of retail adjustment and reform. It shares the same core spirit as what companies like Pang Dong Lai and Sam’s Club advocate — namely, treating suppliers well.

Third, category combination is the driving force of retail innovation.

When supply is insufficient, many single-category formats emerge in the market — for example, coffee shops, braised snack shops, bun shops, and so on.

However, single-category formats essentially load all costs (like rent and labor, which could otherwise be shared) onto one category. As the market matures and competition intensifies, this approach gradually becomes less economical.

To optimize the cost structure, categories are recombined, breaking down original format boundaries and fusing into new business types. For example, coffee and tea, once separate, are now increasingly blended. Many braised snack or bakery shops have transitioned from standalone stores to in-store counters within larger, multi-category formats. Discount snack stores, food supermarkets, and various concept stores are all products of category recombination.

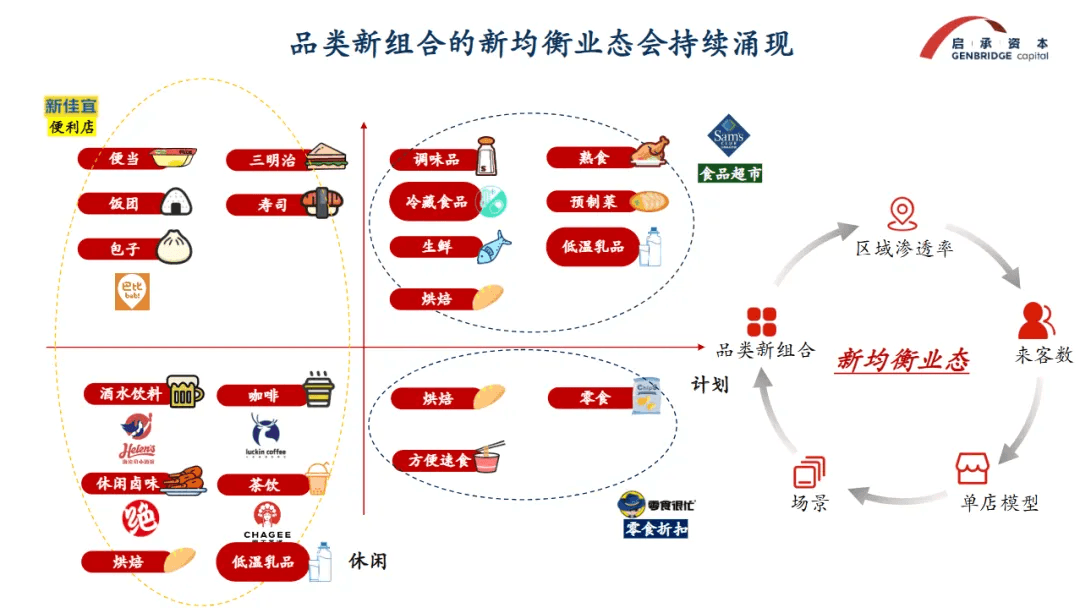

If we map planned consumption versus leisure consumption on horizontal and vertical axes, we get a chart of category combination and format innovation, as shown below.

These new hybrid formats arise from insights into consumption scenarios and are tested and refined in the “trial grounds” of the consumer market. Over time, they perfect their business models, finding the right balance between scale, category mix, and single-store operations.

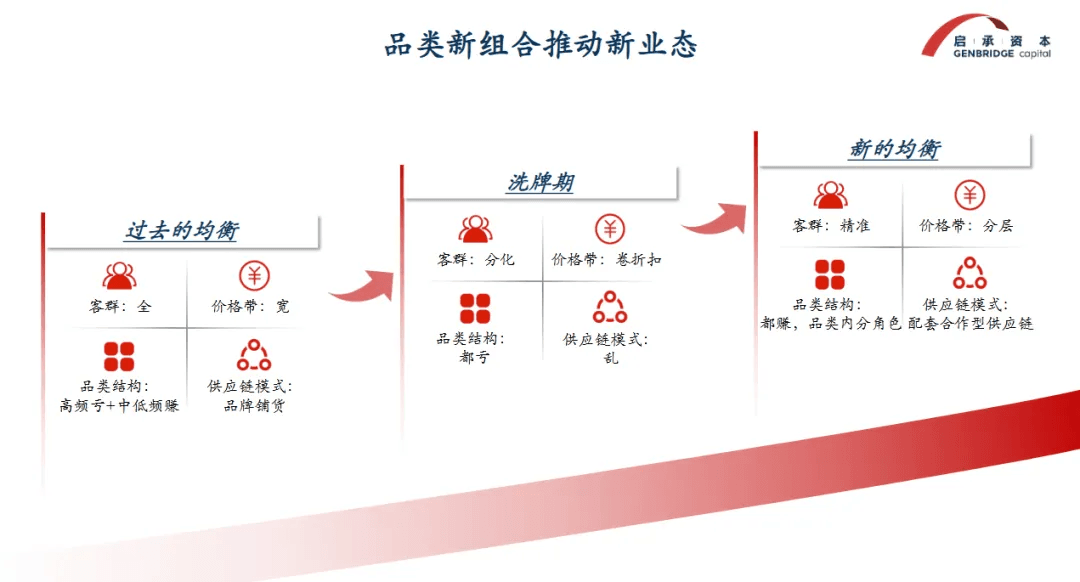

This process represents the retail industry’s shift from an old equilibrium to a new equilibrium. After the reshuffling period, mainstream retail formats will transition away from the traditional model — serving all customer groups, offering wide price ranges, relying on unbalanced category structures and push-style supply chains — to a new picture marked by precise customer targeting, layered price bands, healthy category structures, and collaborative supply chains.

As buyer-centered solutions keep emerging, how should brands adapt to changing channels?

Brands and channels have always stood on opposite sides of the business. While the channel side is experiencing a wave of transformation, the brand side is also facing the failure of old playbooks. Only brands that adapt will avoid being left behind by the times.

So, what opportunities do brands have in this retail revolution?

From scattered to focused product positioning

In an environment of user segmentation, today’s channels are binding ever more closely to specific user groups. Sam’s Club, Freshippo, Pang Dong Lai, convenience stores — each has its own clear customer profile and consumption scenario. When communicating with channels, brands need to abandon blind distribution and instead tailor their value propositions and product innovations to fit the channel’s unique characteristics.

Align with the channel’s category breakthrough plans

In a buyer-driven market, channels that are closer to consumers hold greater leadership. Therefore, brands need to strengthen collaboration awareness and actively consider their roles in the channel’s category plans. We can no longer view a channel statically — category expansion and combination are constantly evolving. Brands that align early with the channel’s category breakthroughs will gain a first-mover advantage.

From zero-sum game to supply-manufacturing alliance

The new consumption environment calls for a new retailer-supplier relationship. Moving from rivalry to mutual benefit is not just the channel’s challenge — it’s also the brand’s challenge. Only by truly integrating into each other’s commercial flows and defining clear divisions of labor can long-term, win-win partnerships be established.

Find niche markets

Whether a new product becomes a hit often involves a lot of luck. But finding a niche market, entering early, and becoming a category leader is an actionable, predictable opportunity. Before the retail industry’s new equilibrium fully arrives, many niche categories are still waiting for brands to fill the gaps.

Costco, Sam’s Club, 7-Eleven — these outstanding companies thrived in mature markets by offering the buyer-side solutions the era demanded, based on deep insights into consumer needs. Ultimately, they succeeded in weathering market cycles.

Chinese retail companies are now also shifting toward the buyer’s perspective, attempting to craft their own answers. Retail transformation is sweeping and powerful, but the test’s answer is never complicated: Whoever can truly meet consumer needs will win.

GenBridge Capital has deeply cultivated the retail sector for many years, continuously investing in various category-killer formats across the food retail space. Our portfolio covers enterprises in provinces nationwide, with over 30,000 stores generating 80 billion RMB in revenue. We firmly believe that China’s retail innovation still holds infinite potential, and we look forward to engaging in deep exchanges with more industry partners to jointly explore buyer-side solutions.